Clubby Monsters: Jeffrey Epstein, Steve Bannon, and Michael Wolff

One way to get scoops about the most horrible people of our time is to socialize with them

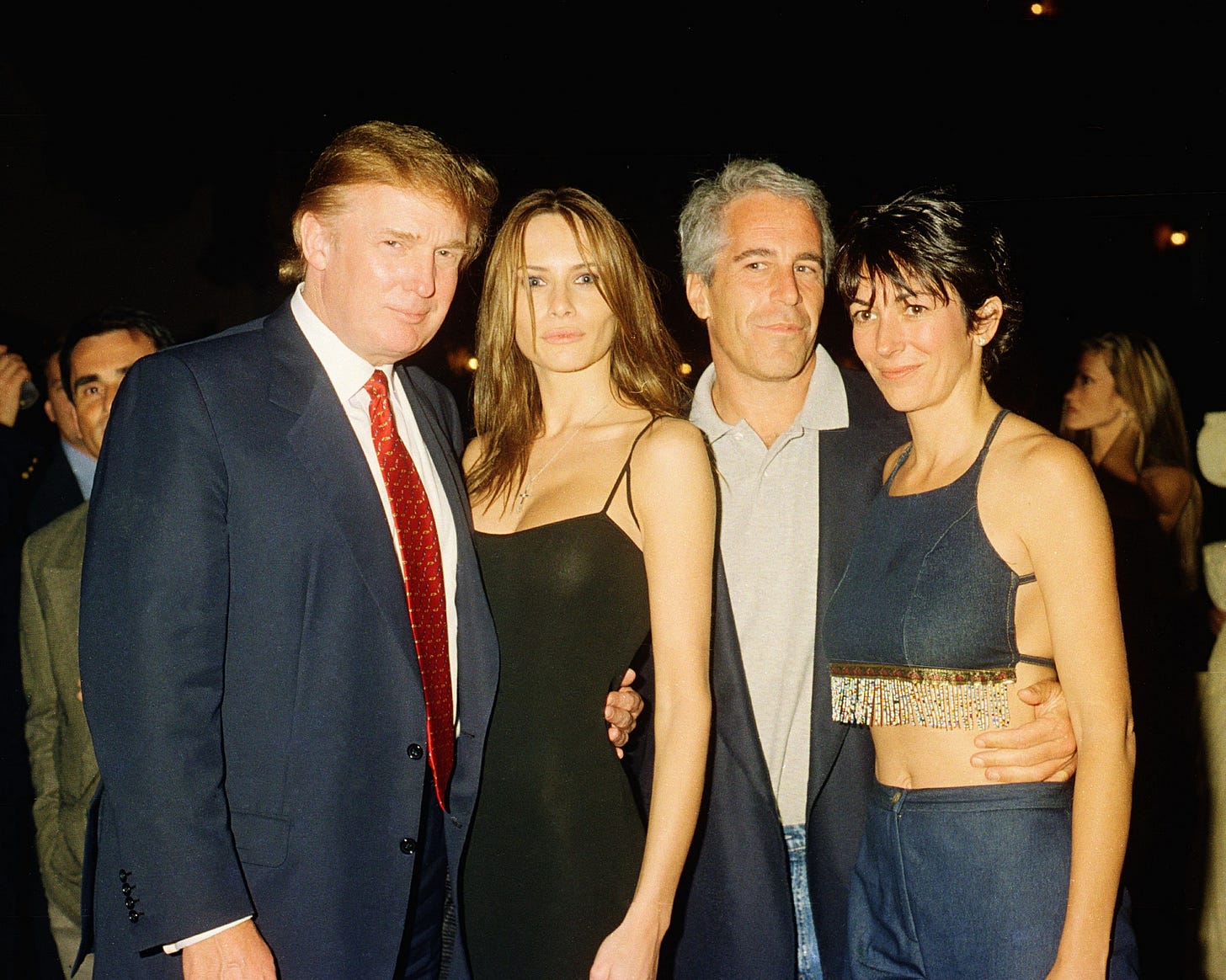

On Sunday, Ben Smith’s fascinating profile of the media-columnist-cum-scandal-monger Michael Wolff ran in the New York Times. The upshot of the profile is that Wolff is often able to report real scoops about various public swines (Jeffrey Epstein, Donald Trump, Rupert Murdoch) because Wolff himself loves to roll around in the mud with them. This is very true and could have been usefully documented with some history about Wolff’s relationship with Jeffrey Epstein that was inexplicably not included in the article.

Smith’s piece helped answer a question that had been bothering me since 2018. I had seen small reports here and there, mainly in the New York Post, that former Trump advisor Steve Bannon occasionally met with Jeffrey Epstein. I tried to drum up interest in the story and encourage those who interviewed Bannon to ask him about it, but to no avail.

As it turns out, Bannon’s relationship with Epstein was even more scandalous than I suspected. Bannon seems to have been spending many, many hours offering pro bono public relations advice to refurbish Epstein’s reputation. Since Epstein worked in a world of markers and chits, of favours done now for favours in the future, one can only have dark thoughts about what Bannon got in exchange for his services.

As Smith reports:

It’s early 2019, a few months before Jeffrey Epstein will be arrested on sex charges, and he is sitting in the vast study of his New York mansion with a camera pointed at him as he practices for a big “60 Minutes” interview that would never take place.

The media trainer is a familiar figure: Steve Bannon, Donald Trump’s campaign guru and onetime White House adviser. Mr. Bannon is both conducting the interview and coaching Mr. Epstein on the little things, telling him he will come across as stupid if he doesn’t look directly into the camera now and then, and advising him not to share his racist theories on how Black people learn. Mainly, Mr. Bannon tells Mr. Epstein, he should stick to his message, which is that he is not a pedophile. By the end, Mr. Bannon seems impressed.

“You’re engaging, you’re not threatening, you’re natural, you’re friendly, you don’t look at all creepy, you’re a sympathetic figure,” he says.

This explosive, previously unreported episode, linking a leader of the right with the now-dead disgraced financier, is tucked away at the end of a new book by Michael Wolff, “Too Famous: The Rich, the Powerful, the Wishful, the Notorious, the Damned.” Mr. Bannon confirmed in a statement that he encouraged Mr. Epstein to speak to “60 Minutes” and said that he had recorded more than 15 hours of interviews with him.

In limning Wolff’s character, Smith repeatedly calls attention to the gossipy writer’s chummy fraternizing with the figures he writes about.

According to Smith:

Magnates seem to think Mr. Wolff gives them their best shot at a sympathetic portrait. He writes, in “Too Famous,” that Mr. Weinstein called him during his 2020 rape trial to propose a biography. “This book is worth millions,” Mr. Weinstein told him, according to Mr. Wolff. “You keep domestic, I’ll take foreign.” As for Mr. Epstein? “He wanted me to write something about him — a kind of a book — it wasn’t clear why,” Mr. Wolff told me.

In the case of Epstein, I wish Smith had gone back to an extremely important 2007 article by Philip Weiss that ran in New York magazine. That earlier piece documents just how close Wolff and Epstein were in the late 1990s and early 2000s. In 2003, Wolff even tried to rope Epstein into a business partnership. As Weiss reports, “In 2003, [Epstein] became a discreet confidant to Wolff during the period when Wolff was involved in a bid for New York Magazine. Sometime after that, Wolff saw the financial architect in his office at 457 Madison Avenue, the Villard House, where Random House once had its offices.”

An earlier New York Times article from 2003 (by the .late, great media reporter David Carr) described Wolff as organizing a bid to buy New York magazine in partnership with mogul Mortimer Zuckerman as well as “Nelson Peltz, a billionaire investor whose Triarc Companies owns Arby's restaurants; Jeffrey Epstein, a money manager with his own claim to the billionaires club; Donnie Deutsch, chief executive of Deutsch Inc., who sold the advertising agency for hundreds of millions of dollars several years ago; and Harvey Weinstein, co-chairman of Miramax films.”

Just to be absolutely clear: Wolff tried to engineer a business partnership with Jeffrey Epstein and Harvey Weinstein to buy a magazine.

In 2003, Epstein was still in the good graces of the law. He wasn’t arrested until 2005. But Wolff continued to socialize with Epstein even after Epstein’s arrest and public awareness of Epstein’s sexual abuse of minors.

As Vicky Ward reported in The Daily Beast in 2019, “A few years ago the journalist Michael Wolff wrote a profile of him for New York magazine that was meant to ‘rehabilitate’ Epstein’s image and would tell of all the billionaires who still, secretly, hung out with Epstein. The piece had ‘fact-checking’ issues and never ran.”

Alex Yablon, a former fact-checker at New York who nixed Wolff’s story, explained on twitter what happened:

Fun fact: I was the checker who killed it! One of my weirdest fact-checking experiences.

Wolff let Epstein dictate the the piece. He made some agreement that all fact questions would go through Epstein and only Epstein. In the piece, Wolff reported various powerful men still hung out with Epstein - but gave me no proof. I was not allowed to call them for comment.

Not surprisingly, NY Mag's lawyers weren't thrilled about a story that alleged various rich and potentially litigious men socialized with a sexual predator without any proof or calling them for comment. As I recall the editor wasn't even aware Wolff had made this agreement.

This is really more of a Michael Wolff story than a Jeffrey Epstein story.

In 2019, New York Times reporter James B. Stewart described an interview he had with Epstein the previous year: “About a week after that interview, Mr. Epstein called and asked if I’d like to have dinner that Saturday with him and Woody Allen. I said I’d be out of town. A few weeks after that, he asked me to join him for dinner with the author Michael Wolff and Donald J. Trump’s former adviser, Steve Bannon. I declined. (I don’t know if these dinners actually happened. Mr. Bannon has said he didn’t attend. Mr. Wolff and a spokeswoman for Mr. Allen didn’t respond to requests for comment on Monday.)”

It’s instructive to go back and re-read Philip Weiss’ 2007 account, which quotes Wolff speaking at length about Esptein as if he were a kind of charming rogue:

Vanity Fair columnist Michael Wolff met him in the Internet bubble, in the late nineties, when Epstein invited him and a group of scientists and media types to fly to a conference on the West Coast in his beautiful 727.

“It was all a little giddy,” Wolff says. “There’s a little food out, lovely hors d’oeuvre. And then after fifteen to twenty minutes, Jeffrey arrives. This guy comes onboard: He was my age, late forties, and he had a kind of Ralph Lauren look to him, a good-looking Jewish guy in casual attire. Jeans, no socks, loafers, a button-down shirt, shirttails out. And he was followed onto the plane by—how shall I say this?—by three teenage girls not his daughters. Not adolescent girls. These are young, 18, 19, 20, who knows? They were model-like. They towered over Jeffrey. And they immediately began serving things. You didn’t know what to make of this … Who is this man with this very large airplane and these very tall girls?”

In the article Weiss quotes Wolff as comparing Epstein to Hugh Hefner and saying, “He has never been secretive about the girls.” Wolff added: “At one point, when his troubles began, he was talking to me and said, ‘What can I say, I like young girls.’ I said, ‘Maybe you should say, ‘I like young women.’ ”

Ben Smith asks, “So what is it about Michael Wolff that has brought him so close to the egomaniacs of our time?” Smith’s answer: “If I had his confidence about getting into other people’s minds, I’d say it was because they see themselves reflected, maybe even envied, in his large eyes, which open a little wider when he wants you to keep talking.”

In the case of Epstein, no such speculation is needed since we have evidence of very material connections: Wolff socialized with Epstein, tried to become business partners with Epstein, and wrote a magazine piece which went unpublished but which tried to whitewash Epstein’s reputation. One way to understand this story is to realize that Bannon and Wolff had essentially the same relationship with Epstein.

The mirror metaphor is imperfect. More accurately, he belongs to the same small social club as his subjects. He’s like a club member who is gossipy and occasionally drops salacious information for the wider world to overhear. The value of the gossip shouldn’t blunt any moral judgements about Wolff himself.

Share and Subscribe

If you like this post, please share:

Or subscribe:

Journalists are supposed to cover the news, not make the headlines. Sadly, Wolff crossed that line too often to be trusted as an objective source.