Funding a Cruise through Autocracy

Some right-wing writers have a genuine love of autocratic regimes but junkets, payola and swag sweeten the deal

The ongoing romance of American reactionaries with Victor Orbán’s Hungarian nationalism is overdetermined. In a previous post, I traced out some of the ideological reasons (xenophobia, homophobia) for the right-wing media elite’s newfound fondness towards the Budapest autocrat. But as so often in life, love and money aren’t so easy to keep apart. While there’s genuine shared affinities binding Yankee and Magyar turn-back-the-clockers, the matter of financial incentives shouldn’t be overlooked.

The New York Times reports that Orbán’s regime has been actively trying to woo American right-wingers with lobbying efforts, citing the prominent case of American Conservative writer Rod Dreher and Fox News host Tucker Carlson. Dreher is currently in Hungary on a paid fellowship while Carlson “himself has a family connection with the Hungarian leader — his father, Richard Carlson, is listed as a director of a Washington-based firm that has lobbied for Mr. Orbán in the United States.” The Times clarifies that there’s no evidence that the elder Carlson’s business ties are influencing Tucker Carlson’s on-going odes to Orbán.

One could add that the late American political consultant Arthur J. Finkelstein served as an important bridge, with his distinct financial interest in the promotion of Orbán. Finkelstein pioneered the pattern—used by the likes of Paul Manafort—of building a client list in both Washington and among foreign autocrats, allowing them not just to make money from both sources but also to serve as a back-channel between American political activists and various dictators.

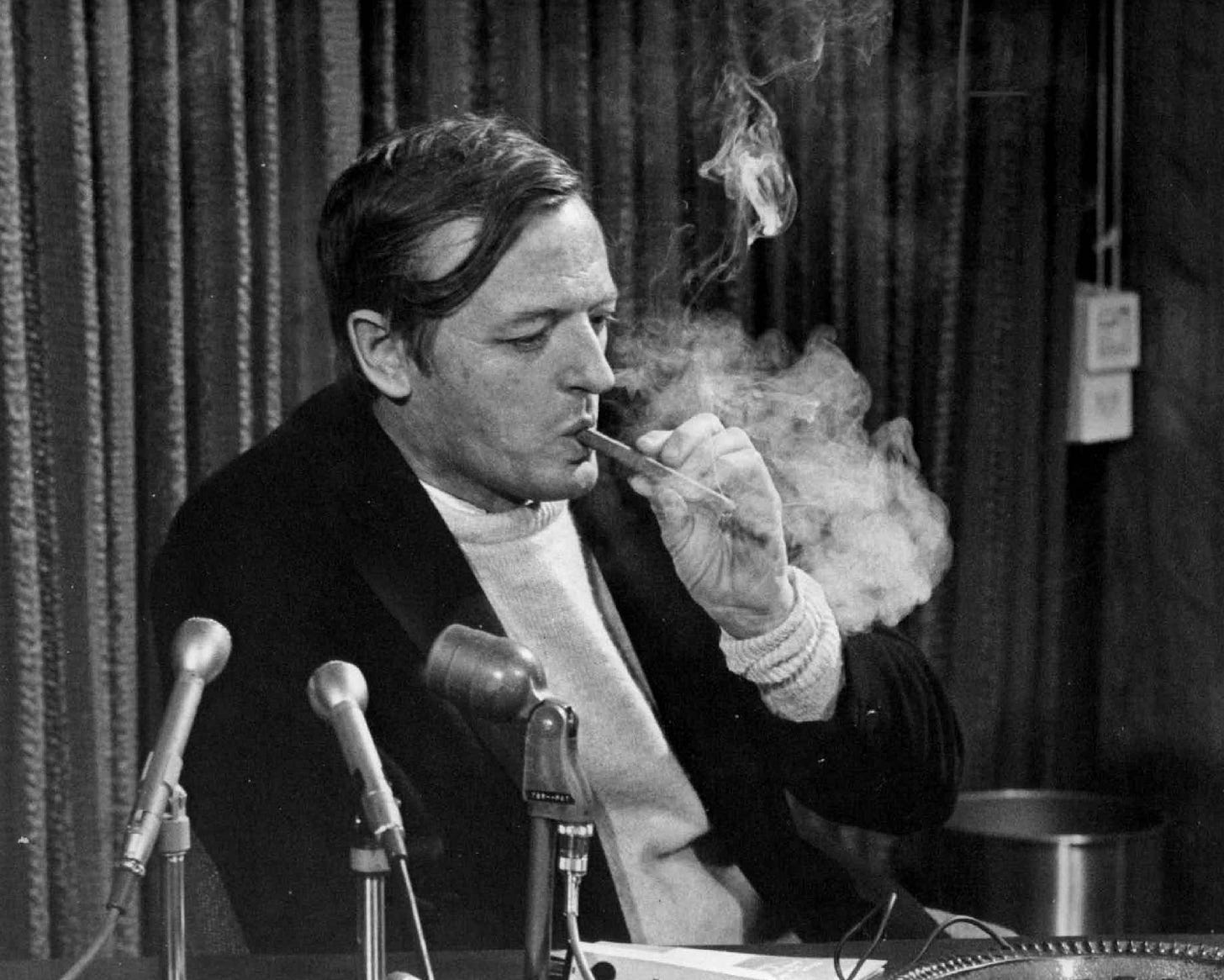

There’s ample historical precedence for all this, of course. Throughout the Cold War, various right-wing governments (notably apartheid South Africa, Taiwan, South Korea, and Pinochet’s Chile) lavished funds on junkets for foreign journalists. They found the National Review crowd was an easy one to win over, sometimes in ways that skirted over issues of ethics. In his 1988 biography of William F. Buckley, John Judis documents how Buckley had worked behind the scenes with his friends Marvin Liebman and Nena Ossa, an agent of the Chilean state, to organize the American-Chilean Council (ACC), a putatively private group.

As Judis writes:

Buckley's determination to defend Pinochet's regime reflected his own upbringing and the priorities of his generation, but it took him farther from what was becoming the center of conservative agitation. In writing about Pinochet—and in soliciting articles for National Review—Buckley also showed a recurring tendency to ignore the canons of objective journalism when he believed that the struggle against communism was at issue. And in helping Liebman and Ossa set up a lobby linked to the Chilean government, Buckley demonstrated a curious ignorance of the law requiring agents of foreign governments to register themselves and their organizations with the Justice Department in Washington.

Thanks to the largess of the ACC, many National Review writers (notably William Rusher, Robert Moss, John Chamberlain, and Jeffrey Hart) enjoyed lavish junkets to Chile, which resulted in articles extolling the dictatorship.

Ossa and others in Pinochet’s camp were delighted that these writers ignored evidence of the regime’s brutality. “Fortunately he seems to be enough to the Right to understand that he cannot possibly write all he sees and hears,” Ossa enthused about an article Moss had written. “His fight against Marxism is much more important than being a journalist.”

Even more seriously, the connection with the ACC influenced how National Review covered the story of a 1976 terrorist attack in Washington, DC. Pinochet had ordered a bombing that resulted in the killing of Orlando Letelier (an exiled Chilean diplomat who was critical of Pinochet) as well his assistant Ronni Moffitt. Moffitt’s husband, Michael, was badly wounded in the attack.

In covering a terrorist attack on American soil, National Review followed Pinochet’s propaganda line and argued that it was the work of Marxists. Jeffrey Hart, fresh from luxury vacation in Chile funded by the ACC, wrote in March 1978 that, “At the time that Letelier was blown up by a bomb in Washington, he had become entangled in international terrorism and was receiving funds through Havana.” Buckley wrote many columns defending Pinochet, one of which argued “there are highly reasonable, indeed compelling, grounds for doubting that Pinochet had anything to do with the assassination.”

National Review publisher William A. Rusher (1923-2011) was the king of the dictatorship junket. Rusher loved to take money from governments like South Africa, Taiwan, and South Korea (back before those regimes democratized) to make a visit and write travel brochures disguised as journalism.

David B. Frisk describes these travels in his 2012 biographyIf Not Us, Who?: William Rusher, National Review, and the conservative movement:

He had been accustomed to lengthy overseas vacations owing to Buckley’s “very nice” rule that both he and the publisher could take an indefinite amount of time off whenever they wished. To an extent, these vacations mixed business and pleasure. In late 1967, Rusher had initially planned only another trip to Tai-wan. Buckley either told him to visit or reinforced his interest in visiting (“I would certainly include”) South Vietnam and most of the other countries that ended up on his itinerary, subsidized by NR and the anticommunist Asian American Educational Association. Rusher should please learn what he could in the way of “news, contacts, local color and travel data” about the Far East and the Southwest Pacific.

Rusher sometimes travelled with younger friends like Daniel McGrath, an advertising executive, for these trips. As Frisk records:

The only unfortunate thing about getting married in 1976, McGrath recalls, was having to give up the trips. They were “almost like a Ph.D. in the world. Bill was just so knowledgeable about everything, and of course he was well-connected.” Often they met with high-level government officials—especially in Taiwan, where Rusher “was a legend,” and South Africa, whose government he sympathized with and generally defended in the newspaper column he began writing in 1973. Among their vacations was one of the four round-the-world trips (five, counting the wartime sea voyage to Bombay) that Rusher would take in his life. “Bill said it was ‘the right-winger’s ultimate fantasy tour. We only went to countries run by colonels and generals.’”

Rusher and Buckley represent the high-end of conservative grift, with first class travel and four star hotels being the prize. Lower on the economic scale, there are those who simply take cash to echo the line of a dictator. As Rosie Gray reported in BuzzFeed in 2013:

A range of mainstream American publications printed paid propaganda for the government of Malaysia, much of it focused on the campaign against a pro-democracy figure there.

The payments to conservative American opinion writers — whose work appeared in outlets from the Huffington Post and San Francisco Examiner to the Washington Times to National Review and RedState — emerged in a filing this week to the Department of Justice. The filing under the Foreign Agent Registration Act outlines a campaign spanning May 2008 to April 2011 and led by Joshua Trevino, a conservative pundit, who received $389,724.70 under the contract and paid smaller sums to a series of conservative writers.

The Malaysia-gate was a minor story by itself, although it involved a dizzying array of writers and aside from Joshua Trevino. Responding on Twitter to queries about his Malaysian work, Trevino commented, “I’m not even slightly insulted at being told I’m not a real journalist. Feel free, but it ain’t a thing here.” To paraphrase Nina Ossa, The fight against Marxism and the desire to fatten one’s bank account are much more important than being a journalist.

The larger pattern that runs from Buckley and Rusher to Trevino to the current Orban enthusiasts is clear: right-wing attraction to authoritarianism isn’t just a matter of ideology but also personal financial benefit. Of course, it’s only natural for believers in the free market to sell their opinions to the highest bidders.

(Edited by Emily M. Keeler)

Previously in this series: Tucker Carlson and Authoritarian Tourism

Share and Subscribe

If you like this post, please share:

Or subscribe: