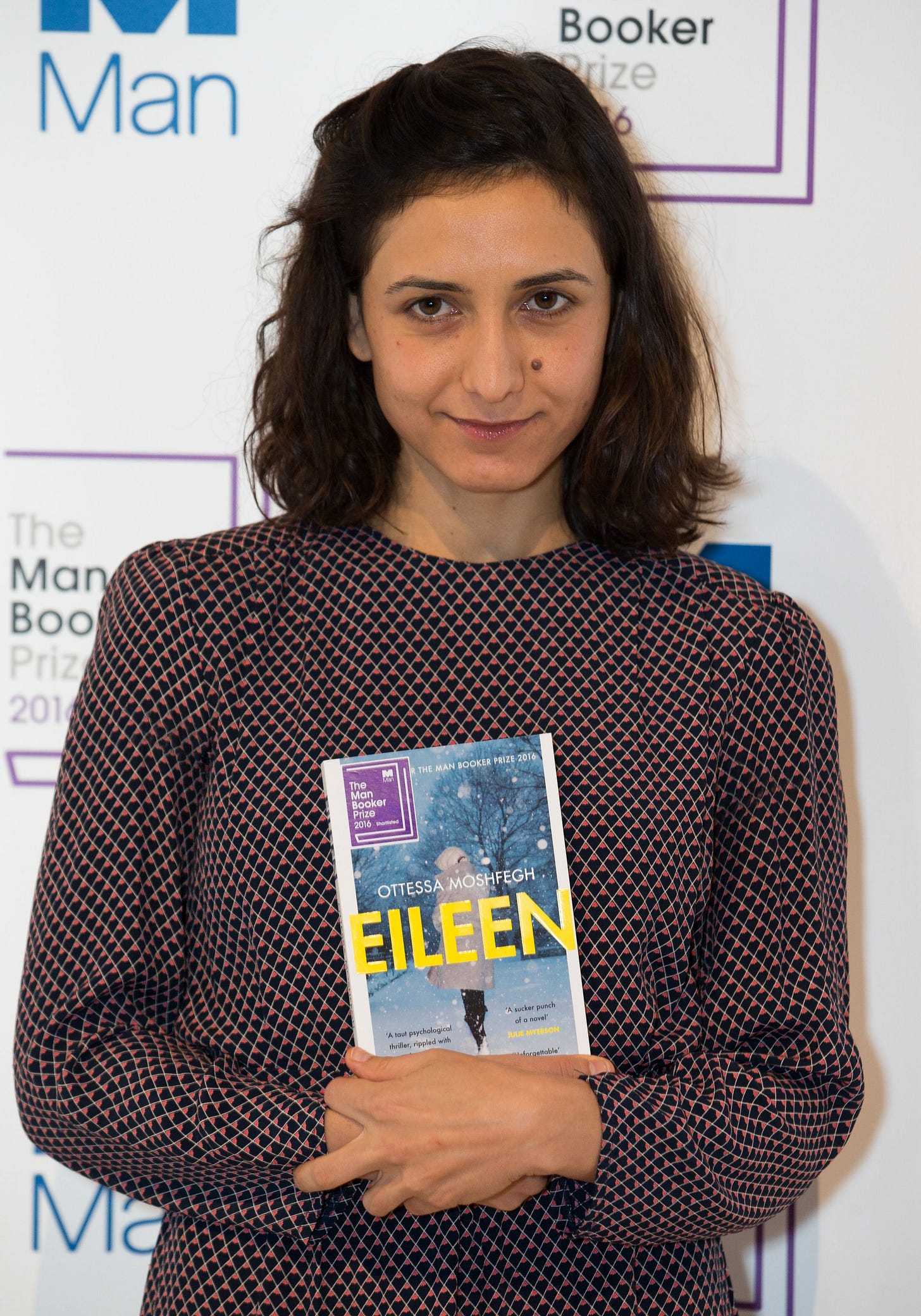

As part of the recent Bookforum symposium on the future of fiction, the novelist Ottessa Moshfegh penned a brief and extremely eloquent polemic against didactic fiction. That it’s being so heavily circulated, especially by fiction writers, suggests that Moshfegh hit on a touchy topic:

I wish that future novelists would reject the pressure to write for the betterment of society. Art is not media. A novel is not an “afternoon special” or fodder for the Twittersphere or material for journalists to make neat generalizations about culture. A novel is not BuzzFeed or NPR or Instagram or even Hollywood. Let’s get clear about that. A novel is a literary work of art meant to expand consciousness. We need novels that live in an amoral universe, past the political agenda described on social media. We have imaginations for a reason. Novels like American Psycho and Lolita did not poison culture. Murderous corporations and exploitive industries did. We need characters in novels to be free to range into the dark and wrong. How else will we understand ourselves.

On one level, it’s impossible for me to disagree with the argumentative impulse behind this paragraph. The novel – indeed all prose narrative, all storytelling – has been, seemingly from the outset, chronically bedeviled by audiences that are excessively literal, that read for instruction and improvement alone, that mistake a tale for a how-to guide, or otherwise conflate the depiction of a character with the advocacy of a program. Storytelling always risks falling into the quagmire of the merely didactic, bogged down by ameliorative concerns that thwart the free play of imagination and shout down attempts to speak the previously unsayable.

So as a rebuke to lazy, unengaged reading, Moshfegh’s mini-manifesto deserves nothing but cheers.

And yet.

I can’t help but think that her statement clears necessary room for the imagination at the expense of accuracy. For the truth is, the novel has a didactic inheritance. Prose fiction, at least in the West, is fusion of various generic traditions that all exist for the sake of social betterment: the religious allegory (Pilgrim’s Progress was perhaps the most widely read English novel for centuries), the satire (Cervantes, Swift), the comedy of manners (Jane Austen) the penitent criminal confession (Defoe), the crusading journalistic expose of societal ills (Dickens, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Zola).

Since Lolita was cited, it’s worth recalling Vladimir Nabokov’s own self-appraisal from a 1971 interview: “In fact I believe that one day a reappraiser will come and declare that, far from having been a frivolous firebird, I was a rigid moralist: kicking sin, cuffing stupidity, ridiculing the vulgar and cruel—and assigning sovereign power to tenderness, talent and pride.”

Even Moshfegh’s desire “to expand consciousness” is a form of social betterment. Every attempt under the sign of modernism to say the unsayable is a rebuke to whatever censorious social forces that keep certain experiences in the dark.

Social betterment, I’d suggest, is an inextricable strand of narrative fiction’s very DNA. It’s possible to imagine other genres and forms – lyrical poetry, music – being amoral. But fiction of any seriousness is always an argument with the world.

(Edited by Emily Keeler).

Share and Subscribe

If you liked this post, please share:

Or subscribe:

the novel is just a modern literary form of storytelling / we've been telling stories since we could speak practically / they have always been about the fantastic the amazing and told in a way that gave people guidance and inspiration / that's what a story is :: conflict resolution / character development / out and back - the hero's journey

I wonder if the world needs or wants more Chuck Palahniuks and Joan Didions and/or fewer Margaret Atwoods and George Orwells?

Nihilism is a legitimate and time tested art form, but doesn't sell as well as the didactic moral narrative. Moral nihilism is edgy, but closer to many of the ugly truths that we all must live with..

Moral nihilism is like a pornographic snapshot into the forbidden aspects of our scary and problematic postmodern Zeitgeist...to be shared salaciously under the table, but never to be seen openly in polite company because even the mere discussion of it is seen as an Act of Rebellion against oppressive and questionable societal mores.

Art and Censure are the Manichaean sweet and sour that most literary fiction critics love to debate. Oft-times you get is a cult following like JD Salinger's, or a dubious one like Ayn Rand's.