Never Trump or Forever Trump?

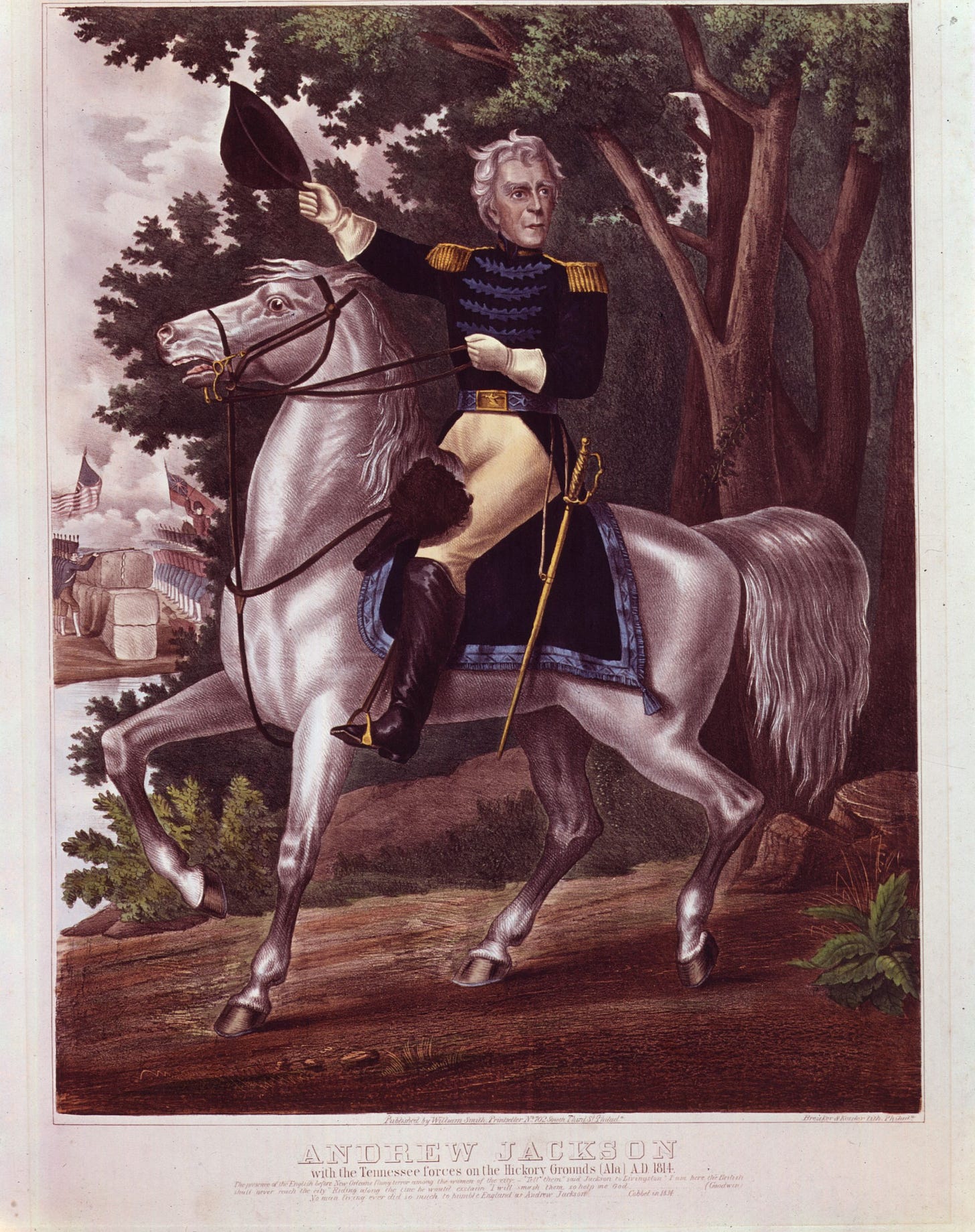

Like Andrew Jackson before him, Trump has remade a national political party in his own image.

Library of Congress/Handout

On May 14, 2019, Joe Biden added a new entry to the ever-expanding anthology of falsified prophesy. Biden predicted, “With Donald Trump out of the White House—not a joke—you will see an epiphany occur among many of my Republican friends.” Trump has left the building but no eureka moment on the need to reject Trumpism is forthcoming. Quite the opposite: Trump’s hold on the Republican Party has only tightened since his election defeat.

Those few Republican voices who dare criticize him for inciting the comical putsch of January 6 or resisted his efforts to overturn the election are now being purged from positions of power. As Vox notes, “At the national and state level, Republicans who challenged Trump’s Big Lie — ranging from Sen. Mitt Romney (UT) all the way down to a member of the Michigan State Board of Canvassers — have either been formally punished or publicly rebuked. The party may not agree on much internally nowadays, but on this point, they march in lockstep: Trump’s falsehoods about the election must not be challenged.”

Trump looms as large over the Republican party as he did when president. Party luminaries like Ted Cruz and Lindsey Graham rush to kiss his ring and sing his praises. If he wanted the party’s nomination again in 2024, he would have a strong claim, since most Republicans, to judge by the polls, insist he won the 2020 election and is in fact the real president. Who better to defeat Joe Biden than the man who (his supporters believe) already has? All the GOP has to do is make sure that they have more loyal partisans in place to settle dispute election results in their favor.

The Trump movement is more dangerous now than ever, because it is explicitly dedicated, post-January 6 putsch, to Republican victories at the expense of democracy.

The fact that the GOP is still under Trump’s shadow is very odd. The norm for American presidents in the last century is that after they leave the stage, especially if they lose an election, they retreat into private life and charitable work. Consider Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama. All became party eminences, some continued to exert backroom suasion on major party disputes, a few commented on public controversies. But none of them had their finger in the pie of active political disputes—including the punishment of enemies inside the party—the way Trump has.

To see a precedent for Trump, one would have to return to the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Andrew Jackson (president from 1829-1837) transformed the Democratic Party into his own brand of roughneck white supremacy, a process that continued for many decades after he left office. Grover Cleveland (1885-1889 and 1893-1897) was the only president to successfully run again after losing an election. Theodore Roosevelt (1901-1909) almost pulled off a similar stunt. He left the White House to a fellow Republican but in 1912 split the GOP in half by running for the Bull Moose ticket. He didn’t regain the presidency and he cost the Republican Party the White House. One reason Republicans cower to Trump is they fear he’s a wild card like Roosevelt and could run as a third party candidate if he’s not propitiated.

Of these precursors, Andrew Jackson is the most suggestive and the most troubling because Jackson had a far-reaching impact on American politics. Trump supporters like Steve Bannon often cite Jackson as a Trumpian figure.

There are some striking parallels. Jackson was an anti-establishment demagogue, whose selling point was that he embodied the rough-and-tumble vigor of frontier fighting men and defied the effete elite of bankers and jurists. Politically, Jackson extolled a vision of America as a herrenvolk democracy, where white men enjoyed equality with each other at the expense of women and people of color. This stood in contrast to the vision of the opposition party, which coalesced in Jackson’s presidency as the Whigs. As compared with Jackson, the Whigs were less hostile to abolitionism, more opposed to the ethnic cleansing of Native tribes, and committed to restraining presidential power by the courts and congress.

I’ve been thinking a lot about Jackson because, at the encouragement of my friend the essayist John Ganz, I re-read Daniel Walker Howe’s monumental history What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848 (2007).

I had read Howe’s book when it first came out in 2006, but re-reading in the Trump era is a different experience. A solid history now seems like a road-map to present-day American politics.

Historical parallels, to be sure, can be overdone. It’s worth bearing in mind that unlike our own period, evangelical Protestants in Jackson’s America, especially in the North, were more likely to be aligned with anti-racist movements than more secular Americans. And that Howe is writing very much in opposition to earlier historians, such as Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. and Sean Wilentz, who painted a romantic picture of Jackson as a proto-populist hero of working class democracy. Still, Howe’s portrait of Jackson as an authoritarian demagogue powered by an ideology of white supremacy is convincing and points toward the roots of Trumpism.

In popular memory, democratic erosion—particularly attacks on voting rights—is associated with the rise of Jim Crow in the South and the backlash to Reconstruction. In truth, there was an earlier democratic backsliding in the first decades of the 19th century. As Howe notes, white men became nearly universally enfranchised in the early decades of the 19th century, while some members of other groups that had previously enjoyed the vote lost it (including women who headed households, free African-American men and Natives). “The less the right to vote came to depend on economic criteria like property ownership or taxpaying, the more clearly it depended on race and gender,” Howe observes. “The United States was well on its way to becoming a ‘white republic.’” Jacksonian democracy was the political manifestation of this “white republic.”

Jackson’s crudeness and vulgarity, combined with his insistence that everyone should bend to his will, were the personification of this white male assertiveness. It was not an ideology of democracy in any true sense but rather an ideology of domination by one group over all others. Jackson proved his right to rule by being authoritarian, by dominating his foes through insults and bravado.

Even reality and truth had to submit to Jackson. Howe relates a story of Jackson defending the honor of Margaret (Peggy) Eaton, the wife of one his cabinet members:

Whether the president really believed in Margaret Eaton's sexual fidelity is doubtful and not even altogether relevant…For Jackson, such matters were issues not of fact but of his authority. Jackson demanded loyalty, and to him this meant acceptance of his assertions, whether he was insisting on Peggy Eaton's chastity or (as he did in the course of another tirade) that Alexander Hamilton “was not in favor of the Bank of the United States.” In the same spirit of privileging his will over truth, Jackson claimed in 1831 that he had received a message from President Monroe through John Rhea (pronounced "Ray") authorizing his conduct in the invasion of Florida. Historians working over a period of half a century have carefully proved the story a complete fabrication.

Trump also believes his will has a higher claim than mere truth. Both Jackson and Trump essentially believe that if a president says it, it cannot be a lie.

Jackson didn’t have so much an ideology as a set of tribal preferences. As the warlord of white men, his word was law. One might think that such a tribal politics would have a limited legacy. But in fact, the Democratic Party was remade in Jackson’s likeness:

Andrew Jackson succeeded in stamping his character upon the Democratic Party, which remained loyal to the policies he had defined even after he left the White House. The party proclaimed itself the tribune of the common white man, as against all other groups in the society, whether of class, race, or gender. In particular, it defined itself, even in the North, as the protector of slavery. Jackson's opposition to abolitionism turned out to be of more long-term significance to the Democratic Party than his opposition to nullification. Jackson's loyal follower, the prominent Pennsylvania Democrat James Buchanan, future president, spoke for the whole next generation of his party. "All Christendom is leagued against the South upon this question of domestic slavery," he acknowledged; slaveholders "have no other allies to sustain their constitutional rights, except the Democracy of the North." Democrats from the North, Buchanan proudly proclaimed, "inscribe upon our banners hostility to abolition. It is there one of the cardinal principles of the Democratic Party."

Howe elsewhere notes:

Andrew Jackson's greatest legacy to posterity was the Democratic Party. His popular appeal had created it; the decisions he reached in the White House became its policies. Where John Quincy Adams, like the framers, had believed in balanced government, Jackson believed in popular virtue—and in himself as its embodiment. A later admirer described the relationship well: "[Jackson's politics] rested on the philosophy of majority rule. When a majority was at hand Jackson used it. When a majority was not at hand he endeavored to create it. When this could not be done in time, he went ahead anyhow. He was the majority pro tem. Unfailingly, at the next election, the people would return a vote of confidence, making his measures their own."

If Trump really is Andrew Jackson Redux, then Trumpism could last decades. The Democratic Party remained the more racist of the two major political parties long after the Civil War and the abolition of slavery. It was only under Franklin Roosevelt in the 1930s and 1940s that the Democratic Party, slowly and hesitatingly, started moving away from overt white supremacy.

The history of Jacksonian democracy certainly suggests that epiphanies of enlightenment are rare. A major party committed to demagogic authoritarian racism can persist for decades. The small dissident forces inside the GOP adopted the slogan “Never Trump.” We need to prepare for the opposite possibility: Forever Trump.

It’s hard to know how seriously Biden himself believed his prediction of a Republican epiphany. As a national political leader, Biden is invested in rhetoric of unity and optimism, so his statement might have been aspirational. But for those of us not running for office, there is no need to make feel-good predictions. It’s better to have a clear-eyed view of reality, free of consoling illusions. Those opposed to Trumpism need to steel themselves for a long war.

(Edited by Emily M. Keeler).