Tax the Gates Fortune

The private whims and personal travails of the ultra-wealthy shouldn't shape social policy.

Getty Images/Staff

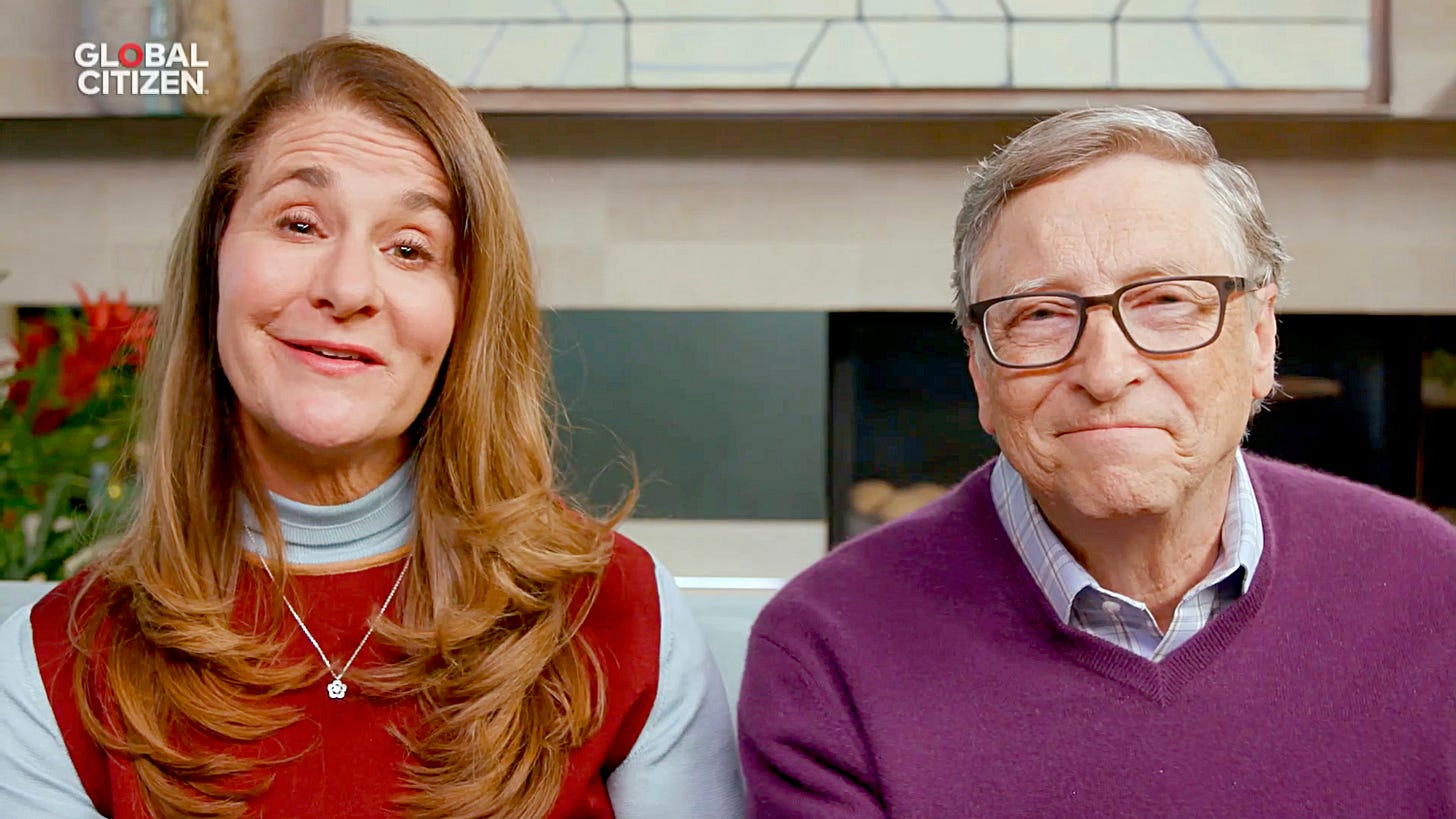

One of the wonders of our age is that you can sometimes see see newspapers editing their articles in real time. On Monday, The New York Times ran a story about the announced divorce of Bill and Melinda Gates. The original abstract for the article read: “The couple’s separation is likely to send shock waves through the worlds of philanthropy, public health and business.”

Within hours, this punchy summary was fudged into much blander words: “The announcement raises questions about the fate of their fortune. The couple helped create the Giving Pledge, but much of his Microsoft money has not yet been donated.”

The rewriting is regrettable. The snappier first formulation forcefully articulated why the Gates divorce is of public interest. Absent the outsized role the Gates fortune plays in shaping global charitable and public health spending, the divorce is overwhelmingly a private matter. It is surely a source of sadness for the couple and their immediate family, with perhaps some implications for Microsoft stockholders, but really not a matter that concerns the broader public.

The editing of the abstract was almost certainly the result of pushback from the Gates Foundation, which was quick to insist to news outlets that the divorce will not effect its operations. But these reassurances ring hollow when you consider the simple fact that the outcome of a divorce is impossible to know in advance. Even if the two parties go into the divorce with every intention of maintaining the Gates Foundation intact, the process of negotiating a settlement could easily shift their thinking.

The changes wrought by a divorce might not necessarily be negative. As the Times reports, “In 2019, Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon, and his longtime wife, MacKenzie Scott, divorced. Ms. Scott received Amazon shares worth $36 billion at the time and immediately set about giving away billions of dollars in direct grants to a variety of progressive organizations.”

But whether the consequences are for good or for ill, it should concern us that the private life of a two people (or more broadly the the charitable giving of a few dozen plutocrats as stratospherically wealthy as Bill Gates) has such a profound influence on social policy.

Before the rise of mass democracy, the fate of kingdoms could often be decided by the domestic affairs of a few dynasties: who Kings and Queens married, how many children were born to these unions, the gender of these children, and how long individual royals lived. Dynastic succession has enjoyed a robust revival in our age of inequality, with the court intrigue of political and plutocratic families setting the agenda of public life in a manner calling to mind the centuries of monarchical and aristocratic rule.

Bill and Melinda Gates have been the leading emblems of do-gooder capitalism, one of the most insidious ideologies used in defence of the status quo. The promise of do-gooder capitalism is that society would allow figures like Gates to accumulate as much wealth as possible (thus maximizing economic growth) and in exchange they’d donate to the public weal (thereby addressing the externalities of economic growth).

Even on its own terms, do-gooder capitalism is a miserable way to organize society. It reinforces the social power of the rich, allowing them to enjoy not just their wealth but also an unjustified feeling of moral superiority. As with the noblesse oblige of old, the social order is stabilized at the cost of turning those around the rich into toadies and beggars.

Further, the ultra-wealthy rarely give away as much as they continue to pile up, so inequality keeps getting worse. As Vox noted in 2019, “Bill and Melinda Gates have given away more than $45 billion through the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which primarily works to combat global poverty. Their work has saved millions of lives. At the same time, the Gateses themselves have just kept getting wealthier.” Bill Gates was worth $50 billion in 2010. As of 2021, Gates’ net worth is estimated at $129 billion. Citing Inside Philanthropy, Vox concluded, “the wealthiest people in the world are sitting on $4 trillion, and accumulating money much faster than they give it away.”

It’s not just a matter of the wealthy not giving enough. It’s also the case that they use their charitable givings to shape the social order with the goal to keep themselves rich. Bill Gates, in particular, has used his donations to push for privatized education and a rigid global intellectual property regime that favors corporate giants in wealthy countries.

As Alexander Zaitchik noted in a devastating New Republic article, Gates is an adamant supporter of monopoly medicine. “The through-line for Gates has been his unwavering commitment to drug companies’ right to exclusive control over medical science and the markets for its products,” Zaitchik observes.

The Biden administration has been resisting the proposal to waive intellectual property rights on Covid vaccines, despite calls to do this from poor countries ravaged by the pandemic. Aside from obvious moral objections, the White House decision goes against America’s own interest, since the longer the pandemic festers the more likely it is that variants will emerge that can break through existing vaccines.

Bill Gates has been hailed as a pandemic hero. This is absurd. Both the uncertainty created in the public health sector by his divorce and, more crucially, his die-hard defence of for drug company monopolies, show that do-gooder capitalism is a failed model. It cannot deliver the social goods it promises. The obvious alternative is a steep wealth tax, which would insure that whatever happens with Gates’ private life or whatever his intellectual whim, a share of his wealth is under democratic control. Since Gates’ immense fortune is itself impossible without the interdependence and shared scientific innovation of modern society, taxing it for the pubic good is only fair.

Love this…“The promise of do-gooder capitalism is that society would allow figures like Gates to accumulate as much wealth as possible (thus maximizing economic growth) and in exchange they’d donate to the public weal (thereby addressing the externalities of economic growth).

Even on its own terms, do-gooder capitalism is a miserable way to organize society.”