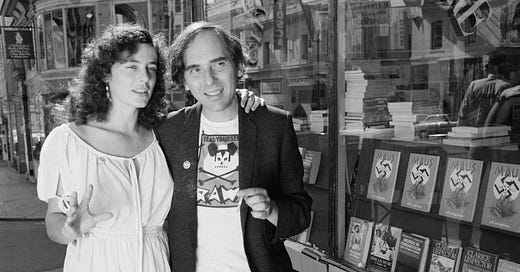

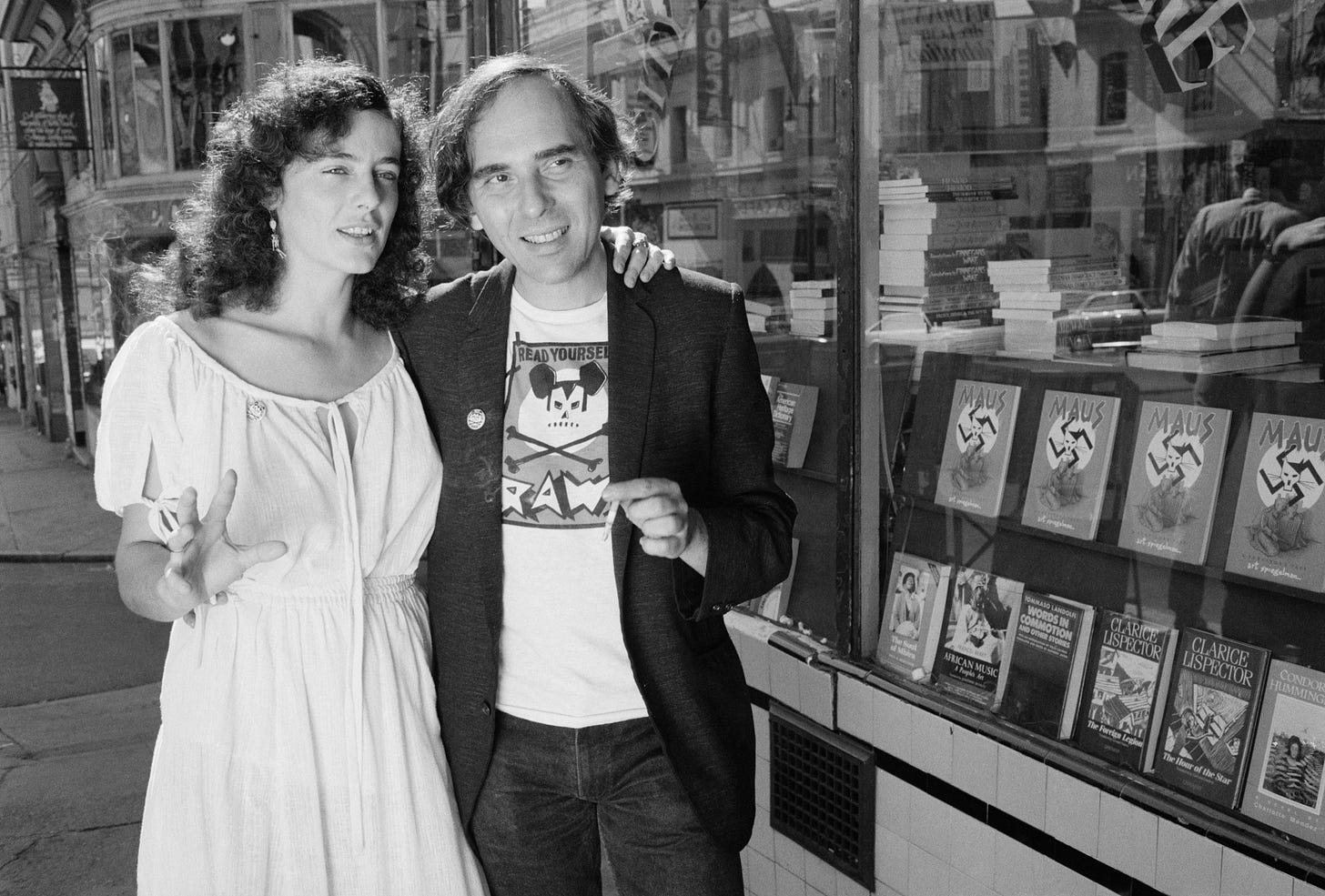

I first became aware of Art Spiegelman’s Maus in the summer 1981 when I was 14 years old. Spiegelman had just started serializing the first chapters of his eventual graphic novel in the pages of RAW, a graphic art magazine he edited with Francoise Mouly. I saw a review of the first issue of RAW in The Comics Journal. I was intrigued by the excerpts The Comics Journal featured of Maus, an anthropomorphic account of the experience of Spiegelman’s father Vladek during the Holocaust told with the Jews as mice and the Nazis as cats. At the time, RAW was a little outside my price range (and carried an amusingly daunting blurb that it was “the graphix magazine of postponed suicides”). I was able to furtively look at some early issues at Pages, a Toronto book store, and fully caught up with Maus by 1986, when the first half of it appeared in book form.

Maus was at the forefront of efforts in the 1980s to push for comics to become more literary. Even at the time, young as I was, I thought Maus was one of the very few really good comics, along with the works of Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez. I would later go on to write a biography of Mouly that tried to situate the importance of RAW and Maus in cultural history.

I shared the book with my school friend David Berman, whose father was a Holocaust survivor. David, not at all a comics person, was also very impressed by it, as were his parents. I remember David telling me how much the cantankerous relationship between Vladek and Art Spiegelman mirrored his own relationship with his father. One of the advantages of the book was it could be read by both young and old— later on, David’s nephews and nieces read the book as young teens

On Tuesday, the McMinn County Board of education in Tennessee decided to remove Maus, which had been taught to grade eight students, from the curriculum. The minutes of the meeting make for dispiriting reading. They make clear that the reasons the board objected to the book are as much about the history it records as the ostensible reasons (the use of some mild cursing in the form of “bitch” and “god damn” as well as a supposed “nude” image).

At one point, board member Tony Allman says, “It shows people hanging, it shows them killing kids, why does the educational system promote this kind of stuff, it is not wise or healthy.” It’s hard to imagine any honest book about the Holocaust that doesn’t deal with the killing of kids.

Another board member, Mike Cochran, says, “I thought the end was stupid to be honest with you. A lot of the cussing had to do with the son cussing out the father, so I don’t really know how that teaches our kids any kind of ethical stuff. It’s just the opposite, instead of treating his father with some kind of respect, he treated his father like he was the victim.” The scene Cochran is describing is from the end of the first volume, where Art Spiegelman learns that his father had destroyed his late mother’s diaries. Those diaries are important for many reasons, not least because Spiegelman’s mom committed suicide and they might provide clues as to the experiences that led to that tragedy. Art is enraged and fights with his father, saying, “God damn you!” Art yells. “You – you murderer! How the hell could you do such a thing!!”

This is no doubt a harsh scene. It’s also one of the crucial moments in the book, because it shows how the Holocaust shaped the Spiegelman family long after it was over, leaving them with all sorts of unprocessed traumas and fights over memory. To have a scene where the son was dutifully respectful of the father at all times would have been a lie and it would also have destroyed the human meaning of the book, the honesty that made it speak to so many readers.

The board members spend a lot of time talking about what they call the “nude scene.” Tony Allmann in particular is hung up on the fact that Spiegelman once, in the late 1970s, drew for Playboy. “I may be wrong, but this guy that created the artwork used to do the graphics for Playboy,” Allman says. “You can look at his history, and we’re letting him do graphics in books for students in elementary school. If I had a child in the eighth grade, this ain’t happening. If I had to move him out and homeschool him or put him somewhere else, this is not happening.” It’s hard not to escape the suspicion that Allman is conflating graphic novel with the phrase graphic sex.

This all puzzled me because I didn’t remember anything salacious in Maus at all. New York Times reporter Jane Coaston solved the mystery by noting that the “nudity” in Maus is a scene were the prisoners in Auschwitz are stripped naked and beaten.

Again, this is a simple historical reality and the actual photos of the naked prisoners are far more shocking than Spiegelman’s stylized anthropomorphic mice. One of the virtues of Spiegelman’s decision to work with a more abstract style is that it makes it possible to narrate horrific events that become numbing when presented with greater verisimilitude.

In a podcast earlier this week, Alex Shephard and I talked about the many purely fanciful examples of cancel culture that are being touted by pundits: the hypothetical or fictional cancellations of Norman Mailer, Joan Didion, and Blazing Saddles. This cancel culture discourse is incredibly silly but it’s harmful. It promulgates a myth of widespread censorship by progressives which helps cloud over the real types of censorship that do actually happen. The removal of Maus from the curriculum shows us the true face of censorship in a concerted effort to avoid painful historical realities like the Holocaust. Not surprisingly, it comes at the same time as the anti-CRT moral panic which is encouraging the banning of books about slavery and racism. Over the last year, there’s been an upsurge in books being challenged in schools and libraries in the United States, with graphic novels and books about LGBTQ people and people of color being particularly likely to be targeted.

The false narrative of cancel culture is a handmaiden to true censorship.

(Edited by Emily M. Keeler)

POSTSCRIPT: In the above post I accepted the idea that the “nude” pictures in Maus that provoked objection were from the concentration camp scene. But as reader Ben Carlsen points out, it’s more likely the objects were to two panels showing Spiegelman’s mother Anja naked in the bathtub. These panels appear in the comics-within-a-comics section of Maus titled Prisoner of the Hell Planet. I’ll simply note that the strip is drawn in wood-cut style, so highly stylized. The nudity isn’t sexual or gratuitous but crucial to the narrative. And Anja Spiegelman’s story is crucial to Maus’s grappling with the intergenerational and lasting trauma of the Holocaust. Many students will have had suicide in the family and I think a work like Maus helps make the pain and guilt of that experience easier to talk about.

Share and Subscribe

If you enjoyed this post, please share:

And subscribe:

Great post, Jeet. Why don’t progressives launch a campaign in TN that has people going on TV talking about cancel culture? We should Steal the term from the right the way Trump stole “fake news” from the left

In 2016.

The book is not banned or censored. It's still freely available in the school library for any student who wants to read it.